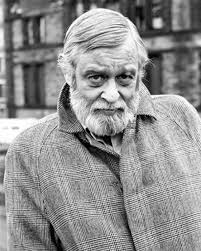

What ever happened to Richard Yates?

Richard Yates has to be one of the most under-appreciated writers of the 20th century. The American novelist wrote nine novels, most of which remain fairly dusty and unread on bookshelves today. In his heyday, though, he was a writer’s writer, praised by contemporaries Kurt Vonnegut and Tennessee Williams as one of the most important American novelists of his generation. Yates’ . In novels like Revolutionary Road and The Easter Parade, he displayed individuals lost and wanting more from their lives, struggling to stay afloat amidst family conflict, job dissatisfaction and suburban conformity.

These books are in essence studies of loss; not in the sense of people losing things they have loved (although tragic events frequent arise in his stories) but rather individuals actually losing, failing to find in modern life what they expect and wish to find. His novels in this way move gradually from hope to despair; optimism to fatalism. They begin with bright-eyed characters, eager for the future and perhaps naive about how it will play out, and end in tragic defeat. Yates’ characters are never able to climb out of the middle-class whole they have created for themselves, torn between the hope of love, success and escape and the failure of it not working out if they tried.

In Revolutionary Road, Frank and April Wheeler talk at lengths about the people they could have been but aren’t. The only Yates’ book to receive a significant amount of attention outside the literary community, Revolutionary Road was a roaring success when it debuted in 1961, becoming a finalist for the National Book Award alongside such classics as Franny & Zooey, Catch 22 and The Moviegoer. It is a heartbreaking study of a marriage in crisis. Frank and April both showed artistic promise in earlier years; he was a Greenwich village intellectual, a romantic who holds dreams of becoming a writer, while she was (is) an aspiring actress, a blonde beauty enchanted by artistic dreams and a cosmopolitan life abroad. They toy with the idea of giving up suburban life to follow through on their romantic dreams of moving to Europe, where “people are alive, not like here.” With its artistic extravagance, intellectual history and cosmopolitan environment, Europe represents everything lacking in their humdrum lives. A fresh start at the very least - a chance to press restart and do what they have always wanted to do with their lives, free from the pressures of conformity and neighbourly expectation.

Yet Frank seems equally attracted to the idea as he is completely repulsed by it. This echoes the broader paradox in his life – he is cynical of what he calls “the enormous, obscene delusion” of their suburban lives, but is clearly terrified of escaping it. He is both dissatisfied with a menial job at Knox Business Systems while grateful of the comfort and stability it brings. Throughout the story, he is wary of turning down promotional opportunities, aware that he needs to “be a man” and make a decent living for his wife and children. We get a sense that his whole life is a performance; even his anti-suburban talk seems undercut by a desire to be different from the crowd, reclaiming April’s belief in their initial romance that he was “the most interesting person she’s ever met.” Ultimately, they don’t make it to Europe. Their marriage descends into adultery, abuse and, eventually, tragedy.

Yates’ writing one of simplicity and economy; there is nothing pretentious about the way his stories unfold. Unlike many others who tried to write the great American novel, his prose rarely draws attention to itself. While he never achieved a wide readership, his stories all have a transparent surface that is highly accessible and ground themselves within the mundane, average world we all know. There is an underlying emotional subtext undercutting his best works, which comes through in the way his character experience small changes of emotion and conflicts of feeling or thought – what is he thinking, what should I say, what does she want me to do? Time moves effortlessly in the background and we see how people gradually change to the point that they hardly recognise themselves anymore.

Yates also gives readers remarkable levels of insight into human relationships and family. The Easter Parade explores the lives of two sisters, Sarah and Emily, as they grow from self-conscious young teenagers to adult women from the early 1930s to the 1970s. The two girls are different in every possible way. Emily is intellectual, precocious and world-wise while Sarah, from a young age more glamorous and pretty than her younger sister, is visibly more conventional and shallow. Their lives also branch off in very different directions. Emily’s curiosity leads her into a string of unsuccessful romantic affairs and stints of employment, while Sarah assumes a domestic role as a housewife to her three young boys and boorish, abusive husband. In spite of their differences, what they share is an endless cycle of regret, unhappiness and a sense of life not living up to what they expected. Although they bond over the loss of their father at a young age, they are never truly able to understand one another. They struggle to express their feelings without judgement and insincerity, unable to break away from their childhood rivalry and petty sibling jealousies. Drifting back and forth freely between their lives and struggles, we are reminded of how often in life we make decisions and choices not because of self desire but in connection or opposition to the world around us. Revolutionary Road explores this more tragically, as Frank and April’s dreams and desires are constantly undercut by their fear of neighbourly surprise and judgement. In the same way, Sarah & Emily each covet what the other has, mainly because they can’t see what darker, sadder realities lie beneath the surface of their everyday lives. The book is fairly brief but Yates is still able to paint a portrait of two lives undercut by sadness and regret. He shows the hope of happiness and potential of success before shutting the door quietly, trapping us within the conformity of modern life.

Yates’ novels are in this way undercut by a constant sense of fatalism, one that isn’t subtle or hidden. They are extremely morbid stories of the downside of modern life, terrifying to readers who might see strains of their own lives or marriages on the page. His characters’ lives are a thin facade; a wall of enthusiasm built to convince everyone else they are full of life, when really they are in decline, screaming to get out, rotting away in sadness. Despite this bleak subject matter, Yates writes beautifully and poetically, as if melancholy was an aesthetic ideal that one could aspire to. His books are both witty and tragic. Like his contemporary John Cheever, he was always able to weave his own narrative voice throughout his books, delivering a strange mixture of humorous anecdotal detachment and sharp, sometimes devastating turns of phrase. Yates doesn’t hold back from showing readers the flaws of his characters, in all their vanity and self-delusion. Yet there is great care directed towards their emotions and we emphasise with these doomed, lonely individuals, aware of the chasm that exists between what we want out of life and what we inevitably get.

Fiction often has a knack for reflecting reality, particularly for writers who inject their own experiences and thoughts into their stories. In this way, there is a cruel irony to how Yates' life as a writer panned out, as his lifelong study of failure through literature seemed to come to define his own lack of success and commercial decline. Just as his characters start off hopeful, talented, optimistic about their future careers and prospects of happiness, Yates debuted to critical acclaim and enjoyed a successful time as a leading American novelist after Revolutionary Road. Kurt Vonnegut called the book “the great Gatsby of [his] time”, while Richard Ford, author of The Sportswriter, said of the novel that it became an important inspiration for writers in particular, a subject that would “invoke a sort of cultural-literary secret handshake among its devotees” when mentioned.

Yet, unable to recapture the same success, his reputation and commercial success dwindled like the lives of his characters, to the point that he was totally out-of-print when he died in 1992 at the age of 66. It’s a reality that is more commonplace than one might imagine; some writers have the appearance of success, constantly receiving praise for their work, even if they are never able to sell enough books to make a decent living or reach a sizeable-enough audience to believe their works ‘matter’. Others are the talk of the town one day and completely irrelevant and unprofitable the next. Yates subject matter didn’t help his commercial appeal in this sense. As Blake Bailey writes in his biography of him, A Tragic Honesty, “to repeat the obvious, most people don't like reading about, much less identifying with, mediocre people who evade the truth until it rolls over them." Perhaps this is why The New Yorker spent three decades rejecting his short stories, before eventually asking his agent to stop sending them.

Like his characters, Yates was also never able to shake out of a state of personal chaos and distraction, living a sad, lonely life subject to periodic mental disturbances and crippling alcoholism. Bailey recounts one such collapse, when in 1962 (only a year after publishing Revolutionary Road) he shocked a writers’ conference by running around naked claiming he was the messiah. Part of Yates’ disturbance was the endless comparison that could be made between him and the other ‘great’ post-war writers. Although he distanced himself from the idea he was part of a literary niche or group, he was constantly resentful of the success of his contemporaries (Bellow, Updike, Cheever etc), who continued to achieve mainstream success with slightly warmer and more uplifting stories while he was slowly wasting away, living off freelance gigs and short-term cash grabs.

For these reasons, Yates’ books have only recently reclaimed their rightful place at the forefront of 20th century American literature. Sam Mendes’ film adaptation of Revolutionary Road went a long way towards this. Shortly after its’ release in 2008, Vintage reissued his entire bibliography, including lesser-known novels such as A Good School as well as short-story collections like Eleven Kinds of Loneliness. Matthew Weiner, the creative genius behind Mad Men, has identified that he wanted to write with the same detailed style as writers like Yates and Cheever, creating an aesthetically beautiful world in mid-century suburbia that is in essence “a mixture of irony, comedy and pain”. Weiner didn’t actually read Revolutionary Road until after writing the pilot episode, and in an interview with Variety he went as far as to say: “If I had read this book before I wrote the show, I never would have written the show. I would not compete with that. I don’t have the balls.” Yet after doing so, the story became a driving inspiration behind the seven seasons of the show. Don Draper lives and walks on Revolutionary Road; he may be wealthier and more talented creatively than Frank Wheeler, but the lack of emotional fulfilment he receives from his work, marriage and life is the same. When the film adaption came out in 2008, comparisons with Mad Men – at the time having just wrapped up its second season – were abundant. Starring Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio, the film was visually stunning and technically brilliant, interpreting the melancholy of Yates’ writing through gorgeous images of 1950s American life. Although it was always going to be hard to translate the deeper subtext and underlying tone of the book to the screen, it still hits hard in its portrayal of marital schism and heartbreak. Scenes with Frank (DiCaprio) on his morning commute, surrounded by similar men in identical suits are instantly reminiscent of Mad Men’s melodramatic aesthetic, which employs beautiful, Norman Rockwell style visuals partially as a way of subverting the empty values of 1950s consumerism and advertising.

It’s not surprising that Mendes was attracted to the source material, given the success of his debut 2000 feature American Beauty, the stunningly poignant story of a mid-life crisis in the suburbs that bears close resemblances to the core themes of Yates’ work. Although taken out of the mid-century setting that Yates’ fiction and Mad Men grounds itself in, it’s a similar story about a disillusioned, cynical middle-aged man reassessing his place and purpose in life. Yet while American Beauty flirts with satire, Revolutionary Road is relentlessly bleak and fundamentally about the tragedy of marriage. As the Wheelers slowly drift apart from each other, exchanging cutting insults designed to hurt the other, the story becomes less about a mid-life crisis as it is reminiscent of tales of marital bitterness such as Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf.

Yates is the forefather of American suburban tragedy. Without him, there would be no Mad Men. It’s unlikely that Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm (based on a novel by Rick Moody), or the realism of Richard Ford and Raymond Carver in the 1980s would have been as powerful and poignant. Many of his contemporaries of course shared his interest in the downside of mid-century suburban conformity, as seen in the Run, Rabbit series by John Updike or John Cheever’s humorous, compassionate style of self-expression. But nothing compares to the melancholic beauty of Yates’ writing, with its strange blend of humorous incites and devastating turns of phrase. No one gave as much incite into the gap between what people think or want to say and what they end up saying.

In the room where he spent the last years of his life, an apartment in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, a quote from politician Adlai Stevenson allegedly sat above his desk: “Americans have always assumed, subconsciously, that every story will have a happy ending.” In the bleak, fatalistic world of Richard Yates, a happy ending almost seems impossible. Books like Easter Parade and Revolutionary Road - like their offspring American Beauty and Mad Men - are able to show that, despite this, there is meaning and beauty in the journey.