Theatre of the Absurd

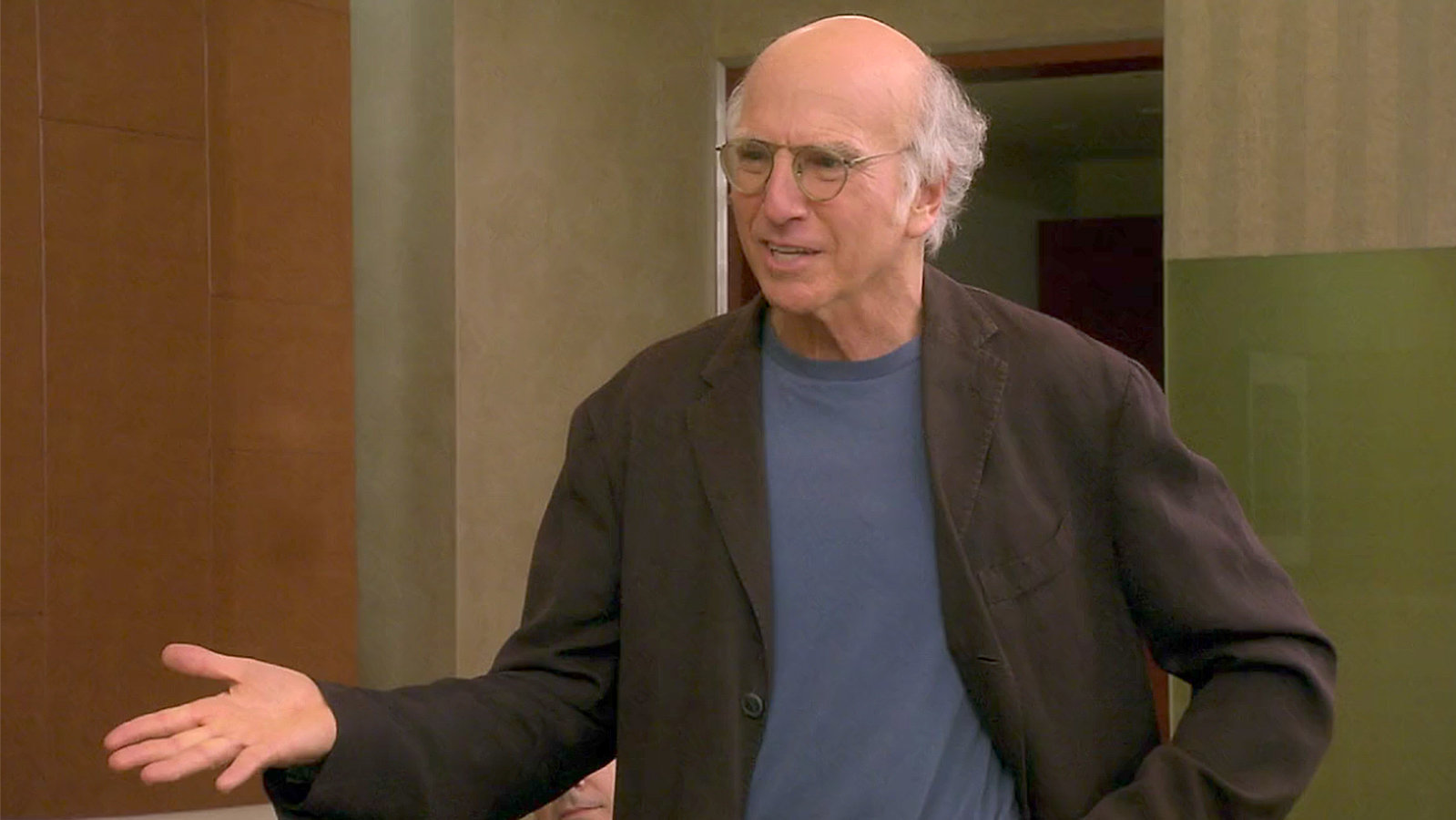

Curb Your Enthusiasm is arguably the most influential television show of the 21st century. Originally airing on HBO in October 2000, writer-comedian Larry David followed up his groundbreaking comedy Seinfeld with a show that fundamentally changed the medium, ushering in a new era of dark, awkward situational comedy based on the absurdity of everyday life. The show depicts the fictionalised day-to-day experiences of David himself, as he navigates an endless array of awkward, cringeworthy social situations and aggressive disagreements with people in his affluent neighbourhood of Los Angeles.

Curb's brilliant humour is driven by a heavy improvisational tone. It famously chooses not to have a script, providing room for the actors to create as they go based on a rough outline of the scene. Yet this only leads many people to underestimate the craft of David’s writing. The carefully and meticulously crafted structure that thrived on Seinfeld was carried over, as seemingly unrelated plot lines happen to cross paths, drawing inevitability closer to an unexpected conclusion which wraps everything up together. Every decision - every action - that Larry makes comes back to bite him but always in ways that seem unexpected and surprising. Sometimes jokes are set up at the start of a season and pop up suddenly with a punchline several episodes later, or recur sporadically as Larry clashes with the various stars that regularly pop up in the show like Ted Danson, Wanda Sykes and his Seinfeld colleagues Jason Alexander and Julia Louis-Dreyfus.

Curb’s comedy lies in the rift between what people really value and think deep down, and what they're allowed to say in order to conform to social conventions. Larry has an uncanny ability to not only remind us of the feelings and judgements we keep tightly bound, but actually make us suddenly aware and conscious of thoughts that we have never considered before ("You know who wears sunglasses indoors? Blind people and assholes"). As he draws directly from the quotidian, the humour also becomes a shared experience that relates to everyone - although, it must be said, the majority of people might not feel that the daily antics of a successful, rich, white man in Hollywood accurately reflects their day-to-day experience. There is in this way a sense of duality about Larry’s character. He is both the common man we all relate to and a ridiculous, inappropriate buffoon. For all the moments we cherish him as the man who says what we’re all thinking, there are just as many where his inappropriateness and foolishness is hard to comprehend. Alexander Aciman wrote in Tablet Magazine in late 2017 that: “the truth is that Larry routinely finds himself in situations that no one on this planet could ever possibly replicate.” What kind of person is so unlucky they happen to be hugged by a child only seconds after they've hidden a bottle of water down the front of their trousers? Only Larry David. At the same time, though, Curb continuously evokes a sense of fearful agony as we worry that someday, maybe, that scenario could happen to us.

Curb’s influence on television is far-reaching. Although David carried over many of the tropes and themes of Seinfeld, the unique deadpan humour mastered by Curb has become a fundamental part of American television, headlined by cringe comedies like Louie, It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia and The Office. Across the Atlantic, the comedy of Ricky Gervais (Extras; The Office) as well as other shows like Peep Show and The Inbetweeners are visibly reminiscent of Curb’s awkward style, while its’ mixture of documentary style shooting and improvisational comedy has been a defining feature of the political satire of Armando Iannucci headlined by In The Thick of It and Veep. In the medium of television, where success often hinges on how likeable and relatable on-screen characters are, these shows feature people who are tragically flawed, selfish and manipulative. They are ruthlessly self-interested and make great efforts to one-up each other, even if they usually come up short. They treat the rest of society as an obstacle or ladder for their own personal ambition, often standing back as detached, cynical observers that seem to exist in a different moral universe. Writing for Vulture in 2014, critic Matt Zoller Seitz went as far as to say the flawed, egotistical characters that emerged at the heart of Seinfeld and subsequent dark sitcoms even “paved the way” for the success of anti-hero characters in dramatic television series, such as Tony Soprano and Walter White.

It has been said that the rise of absurdity in these situational comedies is a reflection of the meaninglessness of modern life and culture. In the 1990s, famous episodes of Seinfeld drew comparisons to the Theatre of the Absurd; absurdist stageplays that emerged in the post-war decades exploring the existential breakdown of meaning, logic, and purpose. Episodes like “The Parking Garage” and “Chinese Restaurant” are effectively one-act plays set in a single room, echoing the postmodern absurdity found in Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot or the surrealist films of Luis Bunuel like The Exterminating Angel. Godot, a story about two clowns waiting for someone that never arrives, was famously summarised by Vivian Mercier as as “a play in which nothing happens, twice.” Seinfeld itself has become famous in popular culture as “a show about nothing”, ever since George and Larry used the phrase in the Season 4 episode “The Pitch” to sell their own idea for a fictional television show that bears many resemblances to the one they inhabit. Yet the overuse of this claim has undermined the true absurdity that sits at the heart of the show. Jerry Seinfeld has repeatedly dismissed it as nonsensical, pointing out in a Reddit AMA in 2015 that “Larry and I to this day are surprised that it caught on as a way that people describe the show because to us it’s the opposite of that.” A lot happens in the 22-ish minutes allotted for each episode - they are just trivial things, drawn from everyday life, perfectly chosen to suit the style of observational comedy that people like Jerry Seinfeld and Larry David thrive on. Rather than exploring the meaningless of life, Seinfeld uses a constant array of meaningless, absurd things to demonstrate just how meaningful life can be.

This is also the underlying premise of most recent dark sitcoms. In both versions of The Office, most of the characters are quirky or bizarre people who derive meaning, endless entertainment and comedic joy not in spite of their dull, boring office environments but rather directly from it. Although characters in these shows behave bizarrely, the action is grounded within the illogical routines and social situations of everyday life. Some shows takes this absurdity much further, taking it away from the everyday towards a world that is much darker, violent and literally absurd. Characters like Kramer from Seinfeld and Charlie Kelly from Sunny are ridiculous human beings, who are so brilliantly eccentric they exist on a different planet and pose limitations to the level we can relate to their on-screen antics. Famously termed “Seinfeld on crack”, most episodes of Sunny involve ‘the gang’ devising ridiculously elaborate short-term schemes, like sell door-to-door gasoline, or seeking vengeance against their rivals, like when they kidnap and bribe a newspaper critic who gave their bar a poor review. It is through such ridiculous antics, though, that they find meaning and a short-lived sense of purpose, away from the realities of their depressing, unachieving lives.

Curb and its' cringe companions in this way follow the trend of the Theatre of the Absurd, transported from the avant-garde stage to the millennial mainstream. Philosophers who have written about ‘the absurd’, most notably French author Albert Camus, have identified that there is a fundamental conflict between what we want from the universe (meaning, order, and logic) and what we are able to find (messy chaos). The absurdity of life arises out of this contradiction. This is essentially how the humour of Curb works. There is a basic incongruity between Larry’s desires and the realities of the world around him, while his frustration always seems to be underpinned by an ongoing desire to apply his own logic and order to things that are illogical or unfair. In his essay The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus offered an important conclusion on how individuals should embrace the meaninglessness and absurdity of life rather than trying to run away from it. He found in Greek mythology the tale of Sisyphus, a king who was punished for all eternity to roll a rock up a mountain only to have it roll back down whenever he reached the top. Camus suggested that this represented the endless struggle of human existence, working and working for no perceivable gain in an absurd world devoid of meaning. For those that did not turn towards religion or suicide to solve this inherent problem, his suggestion was that we must find meaning through this challenge, welcoming it with a smile on our face. We must find the light through the dark. As Camus concluded, “one must imagine Sisyphus happy." This was the same conclusion that many drew about the absurd stage-plays of Beckett, Jean Genet and Eugene Ionesco; despite their perceived meaninglessness and tragic tone, the overall feeling they evoke is not empty but uplifting. Theatre critic Martin Esslin, in his 1965 book Absurd Drama, wrote that these works present audiences accustomed to traditional dramatic structure with a direct challenge:

"...the shedding of easy solutions, of comforting illusions, may be painful, but it leaves behind it a sense of freedom and relief. And that is why, in the last resort, the Theatre of the Absurd does not provoke tears of despair but the laughter of liberation."

Curb is famous for dark moments of cringe and discomfort. When Larry does things like try to justify a poorly executed affirmative-action joke to a dinner table of black guests, pretend to be an incest survivor at a group therapy meeting or congratulate a man on the size of his child's penis, it can be extremely difficult to watch. Yet underneath this pitch-black humour, there is a warmth and optimism that has always underpinned the show. We can often see Larry’s gentle kindness, even though it seems to get missed by everyone on the show. We root for him, whether we see him as the relatable guy or the tragic fool. Despite all the misunderstandings and awkward situations he inevitably gets himself into - despite the bad luck that seems to thwart any hope and optimism - he seems to have so much fun in the process. This is what makes pretty much any scene with Larry and his manager Jeff (played by executive producer of the show Jeff Garlin) hilarious, as we can tell that they are just two extremely funny guys, thinking up lines on the spot and having a great time doing it. You would think that, given his luck, Larry would have a hard time leaving the house. But, following Camus’ advice, he refuses to grow nihilistic by the meaninglessness of modern life. He continues to face up day after day, episode after episode, with a smile on his face.

Some of the most memorable moments of the show are found in Larry’s victories rather than his losses. There are a handful of scenes - often at the end of a season - where many episodes of struggle, misfortune and blame are thrown away by a single moment in which Larry finally gets what he wants. Everything is tied together and there is a feeling of closure and stability. For instance, Season 3 charts Larry’s involvement in a celebrity restaurant venture and their relentless struggle to navigate through the many slip-ups he inadvertently causes that threaten to railroad the entire operation. When Larry becomes outraged at their well-respected chef for lying about wearing a hairpiece, they end up with a last-minute replacement, whose culinary skills are outweighed by the fact that he suffers from a severe case of Tourette’s syndrome. In “The Grand Opening”, the final episode of the third season, Larry finally wins. Everything that has been developing in the previous nine episodes (his struggle to get the restaurant up and running, his wish to have the waiters’ wear ridiculous outfits and answer to customers ringing bells) all come together, resulting in a single moment of awkward comedy that sums up the humour at the heart of Curb. Just when it looked like the opening was going as planned, the chef accidentally launches into an uncontrollable outburst of profanity which silences the room. Larry, instinctively trying to remedy the awkward situation, responds with an equally rude outburst of his own, provoking chaos but saving the day as everyone else in the restaurant slowly weighs in with swear-words of their own. The season ends with the camera zooming in on Larry, grinning contentedly, completely satisfied with himself and his behaviour.

Another example of this comes at the end of Season 4, which sees Larry tapped by Mel Brooks’ to appear in the Broadway musical The Producers, alongside Ben Stiller and David Schwimmer from Friends fame. After many episodes of petty squabbling between Larry and his colleagues, they again make it to opening night, only to have Larry tragically forget his lines in front of a sold-out crowd. When the punters start to file out of the theatre in disgust, Larry saves the day by improvising some comedy, returning them to their seats and kick-starting a hilarious performance of the rest of the play that wallows in its own imperfection and chaos. Once again, the season ends with Larry in charge; this time receiving a standing ovation on Broadway.

While usually Larry's attempts to solve a disagreement or problem inevitably lead him further over the cliff, in both of these occasions he has seemed to make the world around him adapt to his own wishes and standards. He has finally won. He is Sisyphus at the top of the mountain. Having rolled up the rock of social propriety for seasons on end, he experiences a fleeting moment of contentment that overcomes all the absurdity and chaos of life. We know the rock is about to roll down the hill again and he will be in the doghouse for any manner of faux paux. Yet we also know that this struggle is what provides meaning to Larry’s life and the show. Perhaps all of Larry’s struggles have been leading to these redemptive moments, when he can show everyone he is actually a decent person just trying to do his best in a world that is cruel and unfair.

It’s similar to the fact that, in Sunny, for all the infighting, yelling matches, and dark scheming that goes on between different members of the gang, some of the greatest moments are when they all embrace their shared failure in a moment of collective understanding and contentment. At the end of “The Gang Gets New Wheels” - the outstanding episode of last year’s 13th season and up there with the best the show has created, Dennis picks up Mac and Charlie and then Dee and Frank, all running for their lives from the police for various offences involving beat-up children, a traffic accident, and potentially statutory rape. Dennis soothes their fears, calmly telling them “it doesn’t matter. It’s okay. We’re in the Range Rover now. All is well.” As they all nod their heads to Rick Astley blaring from the speakers, the credits roll and the audience is left with a soothing ending that is unusual for such a dark, absurd show. Sometimes these moments are louder and more jubilant. After Charlie is publicly humiliated in a scientific experiment in the Season 9 episode “Flowers for Charlie”, the gang insults the officials giving the lecture, storming triumphantly out of the room and making plans to watch Police Academy as soon as they get home. They all seem so happy to have Charlie back in their lives once again.

Sunny is clearly a very dark show. Cannibalism, grave robbing and blackface have all been featured, while one only has to look at the character development over thirteen seasons to realise it has gotten worse. Dennis has slowly revealed himself to be an actual psychopath (as seen in the video above) while supporting characters like Rickety Cricket have slowly had their lives ruined through their interactions with the gang. Yet behind the dark self-absorption that it is famous for, the show is actually filled with this sort of warmth. Frank and Charlie’s love and care for one another is genuinely heartwarming and, while each episode sees the gang takes great strides to sabotage and humiliate each other, they always end up back together just where they started. Deep down, they seem to feel most comfortable when they are with each other at the bar, within a closed community of delusion and failure.

In this way, in Sunny, Seinfeld and other sitcoms like The Office, the characters face failure and the absurdity of the everyday world together. Yet Larry is completely alone in Curb. No one else seems to understand him or his outlook on life. He pushes the rock up the hill by himself. Perhaps this is what positions the show as the pinnacle of cringe comedy - there is nothing more dark than facing the awkwardness and meaninglessness of life alone. When asked to explain the title of Curb, David remarked that it is inspired by the fact that “we don’t want to see people happy. And we want them, if they are happy, to keep it private and not subject the rest of the miserable world to it. We don’t want to see it, hence; curb it.” But if Larry’s constant failure and inability to socialise appropriately wasn’t undercut by his love of the process – his ability to hang in there in an absurd world devoid of any meaning or fairness - the show wouldn’t work. If Larry never wins, his losses seem inconsequential and devoid of meaning. Instead, one must imagine him happy.