The Long Take: A Cinematic History on the Page

At one point in Robin Robertson's genre-bending novel The Long Take, a war veteran named Walker muses that "the only American history is on film". It's a grand statement, yet one that reveals a lot about the United States, where Hollywood not only holds mythical status but also remains an important way the country is able to self-project in major moments of flux and social change. This is probably no more true than in the case of film noir, the style of filmmaking that emerged in the 1940s, combining moody crime stories with a low-key, shadowy aesthetic inspired by German expressionism. Bleak, bitter and relentlessly cynical, film noir holds the key to unlocking the uneasy psychological atmosphere and mood that emerged in the post-war decades.

The Long Take is Robertson's own homage to these films. It is a monochrome masterpiece laden with the illusory shadows and distorted patterns that lay at the heart of this cinematic style. A finalist for the 2018 Man Booker Prize, it is strange, epic and utterly unclassifiable, told through a beautiful blend of free-verse and lyrical prose. The story traces the movement of Walker, a Canadian veteran of the second world war, as he travels across America trying to make sense of his return to civilian life while searching for the sense of purpose and moral certainty that was stripped of him in the war. Moving from the urban labyrinth of New York to the open, decaying landscape of California, he is witness to a decisive era of fracture and anxiety in American history.

The full title of the novel (The Long Take - Or A Way to Lose More Slowly) refers to a line from the quintessential noir classic Out of the Past, in which Jane Greer asks Robert Mitchum if “there (is) any way to win?” at the roulette table. Quick as a flash, Mitchum replies: “Well, there’s a way to lose more slowly.” Robertson seeks to show that

this is exactly what happened to American society after the war, as the jubilation of victory abroad dwindled in the face of greed, corruption, and xenophobic paranoia at home. While millions of soldiers returned home, further anxieties soon emerged with the spread of communism and the threat of nuclear warfare. Anti-communist investigations relentlessly sought to uncover conspiracy through scours of Washington and Hollywood. Foreign evil had become domestic evil. America seemed to have brought home the authoritarian style of government that it had spent years fighting against, as Walker notices:

“McCarthyism is fascism. Exactly the same. Propaganda and lies, opening divisions, fueling fear, paranoia.”

There was a need for art and entertainment that could dramatise these anxieties and blur the lines between good and evil, right and wrong. Enter film noir, an atypically dark variety within an industry that was historically upbeat and romantic. In these stories, audiences found an America that brought home the brutality and moral complexity of war, only to turn it inwards violently against itself. The idealistic hope of the American dream had soured into a nightmare, one that was bleak and claustrophobic but also mystical and brimming with energy and vitality.

Film noir told a variety of stories. Many were gritty detective stories carried over from the hardboiled fiction of Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. Brooding, cynical tough-guys seeking justice for corruption and evil in a seedy criminal underworld. Others were more melodramatic and focused on the perpetrators of crime, often scheming lovers out to commit fraud and murder as in Double Indemnity or The Postman Always Rings Twice. Today, when we think film noir, we think guns, femme fatales, heists. Yet there are just as many stories that turn their focus away from crime towards unfortunate, disillusioned outsiders (loners, alcoholics, war-veterans) in dark, doomed urban settings. Film historians have been wary of characterising noir as a ‘genre’, preferring to discuss it as a style of filmmaking typified by a particular mood and tone, rather than specific narrative conventions that might underpin a Western or gangster film. The essence of noir is found underneath the surface of crime and violence, in an interior world of confusion, obsession and alienation that mirrored and was grounded in the anxiety of American society in the post-war years.

It was not exclusively a post-war phenomenon. The enduring popularity of war-time releases such as The Maltese Falcon and Laura show that Hollywood was already becoming disillusioned, perhaps belatedly reacting to the economic depression of the 1930s and informed by the growing consciousness of social changes, as well as the dark complexities of war. The ‘noir’ label was itself coined by French critics as early as 1946, when - finally seeing the American films they had missed - noticed the burgeoning darkness and cynicism that had gained a foothold in Hollywood.

Robertson does a great job weave this cinematic history into his novel, effortlessly name-dropping films, actors and dialogue from a vast catalogue of stories. He caters for the cinephiles, including a “credits” section at the end the book providing dates and background information for every reference.

Yet the novel's greatest accomplishment comes through the positioning of Walker as a living, breathing witness to this artistic phenomenon. Film noir becomes the only way the veteran can make sense of his post-war existence. The dark urban labyrinths and moral ambivalence projected on the screen seem to his own alienation and trauma, something he can recognise and relate to in a world that is unfamiliar and strange. As he wanders (“he walks/That is his name and nature”) around Los Angeles, Walker encounters film crews shooting on location, identifies sites as locations for his favourite scenes, and even has chance meetings with directors. Robert Siodmak, director of noir touchstone pictures like Criss Cross and The Killers, says that Walker has "deep focus. Long eyes for seeing. The attention to historical detail raises the novel to an epic scale, as archival photos, a hand drawn-map and endless descriptions of real streets and buildings ground the story within a real time and place. When combined with Robertson’s dreamy poetry, the novel becomes a complex blend of homage, myth, and history.

Although Robertson’s medium is poetry, the story is intrinsically visual, driven by the aesthetic and tone of noir cinema, Robertson achieves the same effect. Walker’s journey is told only through experience; the novel is really just a mammoth collection of individual descriptions, memories and short scenes of dialogue on sidewalks and in bars, offices, train stations and cinemas. Jump-cuts, montage, and holding shots (it’s called The Long Take after all) come through Robertson’s writing as if he were holding a camera, pacing a story that is both fluid and fractured.

Walker's journey unfolds in a way reminiscent of the non-linear storytelling of film noir,with flashback and disrupted editing suggestive of an obsessive connection to the past. Some of the best noirs, like Sunset Boulevard, begin at the end of the story and use narrative voiceover throughout to evoke a sense of doom and tragic fate, forcing audiences to consider the ambiguity of truth and memory. The Long Take inherits this fatalistic bleakness, shifting effortlessly from poetry and prose and dissolving barriers of time and place by establishing connections between Walker’s past and present. Diary entries provide a window into his tortured, confused mind as he interprets the bleak world around him. Robertson also intercuts narration of the present with italicised flashbacks, to Walker's memories of both a romantic, pastoral childhood in Nova Scotia, Canada as well as the blood and chaos of D-Day at Normandy in 1944. The urban jungles of L.A. and New York are a lurking backdrop for this mental schizophrenia, as descriptions of everyday chaos in the streets trigger his memories, particularly the violent ones:

“Cities are a kind of war, he thought. Sometimes very far away then, quickly, very close…”

Robertson’s self-reflexivity and fractured storytelling allows a merging of fiction and reality, as the novel moves naturally from Walker’s own existential journey within the urban jungle (“sometimes it just feels like a labyrinth: that old game of survival and loss”) to poetic descriptions of the noir films he loves, such as Jules Dassin’ 1950 noir classic Night and The City (“Then cut, to a high-angle shot of a man running, chased across an open square shadow and light: this chessboard of fear, nightmare of traps…”). The story also seems to slowly build in meaning and scope. Walker’s diary entries, initially descriptions of everyday life, become brooding ruminations on the moral decline of American society. Flashbacks become more and more frequent and timelines become woven together,different threads within an epic tapestry of memory and trauma.

The Long Take is in this way reminiscent of the kaleidoscopic style of the poet-novelist Michael Ondaatje, whose own works are pastiches of memory, myth and history. When reading Ondaatje’s novels, one is overwhelmed by the beauty and intensity that seems to flow out of every sentence. Everything is soaked in emotion and symbolic meaning. Like Robertson, Ondaatje also makes inventive use of non-traditional narrative structure - blending stories, timeframes and historical fact to create deep, interconnected universes that seem equally grounded in fiction and reality. His recent best-seller Warlight shared The Long Take’s shadowy post-war setting and mirrored its’ fluid format. Just as Robertson cuts between Walker’s everyday life to intense memories of war and childhood, Warlight is in essence a series of adolescent recollections of a foggy, blitzed London that quietly shifts between time and place to show the passing of years and the free association of memory. For these authors, written stories can be told through the collection of stark cinematic imagery - individual frames and scenes - that exist as mere fragments of a mystifying, historical epic.

The Long Take also illustrates the fluid, ambivalent feelings that come with being an outsider in an unfamiliar place. Walker travels across America (“the ride west, like his life, going by too fast”) searching for community and a place within an unfamiliar post-war society. He is witness to the strange contrasts that defined these years; optimism and gloom, hope and despair. Robertson’s writing, with its relentless energy and jazzy, free-verse inherited from the beat generation of poets, allows one to feel the buzz and enticing sordidness of the post-war American metropolis:

“This was city life: he walked for hours, up and down Main, watching it flex and swell, feeling the crowd’s edge of fever and delirium, friction and threat: its black pulse”.

When Walker arrives at L.A.’s Union Station after a long train journey across the country, he perceives the city as “the bright gateway to a new future - a new American future, it said - a paradise in the sun.” His first impressions are typical for heroes heading West. Since the days of the Gold Rush, California has held a special place in the American imagination, representing a place where luck, opportunity and hope could lead to a more fulfilling life. Yet Robertson shows the dark side of this paradise, presenting Los Angeles as a city of corruption and chaos behind the Art-Deco glitz and glamour of Hollywood; a strange mix of old and new, rich and poor, beauty and squalor. Walker’s chance encounters with film crews and famous locations are consistently juxtaposed with the struggles of the poor and homeless downtown on Skid Row.

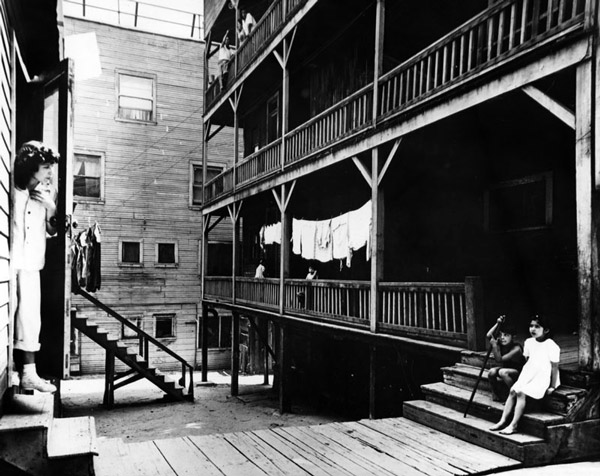

Robertson also plants his protagonist as a witness to the urban destruction and modernisation that transformed Los Angeles, and all American cities, in this era, when entire suburbs were demolished to make-way for more buildings, freeways and car parks. The Truman administration signed into law the Housing Act of 1949, funding city projects to clear slum areas to make way for private development and the construction of clean, lower density public housing. Along with the GI Bill, this was part of a series of sweeping reforms in the post-war years that sought to build the American middle-class through suburbanisation, using tract housing to create planned communities such as Levittown, New York and areas of the San Bernando valley in California. In Bunker Hill, Walker's neighbourhood, the rise in squalor and crime fueled by the Great Depression had condemned it to destruction, even though it had historically been an area of luxurious Victorian villas and timeless architecture. As part of the Bunker Hill Urban Renewal Project, 7321 housing units were demolished to make way for car parks and private private buildings, many of which remained empty or scarcely used. Using this history as a canvas, Robertson paints the portrait of an artificial city that has crushed heritage and community in the pursuit of the new:

“Los Angeles is like a fridge or a car now, it’s built to break, so it’s temporary/When you get tired of your world you just upgrade.”

This was the same L.A. depicted in the neo-noir classic Chinatown (1974), a rotten, messy shanty-town wasteland driven by the corrupted planning process and greed of the corporate elite. Walker initially flourishes as a newspaper reporter, writing about the homeless and trying to expose the civic corruption that has doomed the city. Ultimately, he can’t escape the claustrophobia and chaos that surround him. He spirals into alcoholism and mental disarray before resigning himself to his fate: “I can stop now, he says, putting his mouth to the mouth of the bottle. 'I’ll make my city here'.” Robertson shows how the American metropolis fails, closed off to outsiders who are poor or ill or homeless or not white.

The Long Take is also fundamentally a story about a war-veteran and the struggle of returning to civilian life. Many films released in the immediate post-war years explore this theme, the most famous being William Wyler’s 1946 classic The Best Years of Our Lives. The film showed the struggles of three ex-servicemen who, coming home to small-town America to find an unfamiliar and irreparably changed society, have to deal with the anxiety and fear associated with resuming everyday life. It clearly struck a chord with many Americans, becoming the highest-grossing film in both the U.S. and U.K. since Gone With The Wind and dominating the 1947 Academy Awards with seven accolades. Yet although the story’s presentation of an unresolved and messy post-war America was a far cry from the optimism of Hollywood musicals or patriotic war films, the tone of the film is cautiously optimistic and underlined by a feeling of love and warm compassion. Rather, the dark film noirs that began to emerge at the same time focused on the impact of war on the American psyche, exploring the instability and internal chaos that many veterans faced, traumatised by the horrors and stress of combat. They also presented a much bitter and morally ambiguous alternative to the 'veteran adjustment' story, as men returned from war to learn news of their wives’ infidelity or death, or betrayal by a friend or business partner.

War-veterans were in many ways the perfect model for the flawed, socially alienated male protagonist that lay at the heart of every noir film. Having witnessed the brutality and horrors of war, veterans were no stranger to the violent world depicted on-screen. Many also faced internal crises of identity as they struggled with their new status as an outsider, lacking in clear priorities or moral certainty and plagued by memories of their past. In one scene in The Long Take, Walker overhears a fellow veteran refer to himself as "nobody's friend - the man with no place" - one of Robertson's several references to the classic 1947 film Ride the Pink Horse. And this was true for many veterans, who faced the threat of homelessness brought on by PTSD, substance abuse and the breakdown of family relationships. In films like Cornered (1945), The Blue Dahlia (1946) and High Wall (1947), veterans were vagrants, struggling with brain-damage and alcoholism and quickly resorting to murder and violence to reclaim control over their civilian lives. Through the sordidness of urban crime and violence, these films were also able to explore the thin moral line that lay between killing as a state-sanctioned act of war and murder as a punishable offence in civil society. All these issues plague Walker, as much a casualty of war as those that died alongside him on the beaches of Normandy.

Film noir has maintained its freshness to modern audiences because it promotes a style rather than just a theme. The critical and financial success of recent neo-noir pictures (the films of Nicolas Winding Refn & the Safdie Brothers in particular) prove it is a timeless mode, able to be translated between genres and from generation to generation. Though firmly rooted in a historical time and place, The Long Take also seems apposite today, given it not only echoes the timeless way these films were presented and told, but is also primarily concerned about the perennial tale of greed and corruption having the capacity to crush individuality and hope. PTSD, alcoholism, homelessness and a lack of affordable housing remain as critical as ever, particularly in America where inequality is intrinsically tied to what colour one's skin is, how much healthcare one has access to, or whether one has been to war. And Walker's journey is in many ways the quintessential story of the outsider in any time or place, confused and alone in a society that is brutally unforgiving to those on the fringes.