Sally Rooney & The Problem with the 'Generational Novel'

Since the release of Sally Rooney’s debut novel Conversations with Friends in 2017, claims that the young Irish novelist is the “voice of a generation” have been so common that they have almost lost their meaning. The twenty-seven-year-old Rooney, whose first two novels are chiefly about young students on the cusp of adulthood, has come out of nowhere to rise to stunning literary fame. Conversations followed a duo of female college students (and ex-lovers), Bobbi and Frances, who become involved with an older married people whose luxurious lifestyle they both covet and criticise. Her second novel Normal People was the book of 2018, selling like hotcakes and wowing critics and fans alike with her exploration of the highs and lows of young adulthood. It is a love story more than anything else, a tale of a close connection between two young people, Marianne and Connell. As they finish their final year of high school in the west of Ireland and move to study at Trinity College, the prestigious university in Dublin, their relationship stutters through a series of on-and-off-again flings.

The success of these books has led many to identify something visibly new within contemporary fiction; the arrival of a millennial voice. Rooney, perhaps more accurately than anyone else, seems to be able to define the realities and problems facing young adults today - the way they understand themselves, their peers and the world around them. Her world is a delicate balance between hope and despair. Characters speak intellectually and with promise, but stumble through unpaid internships, awkward sex, social anxiety, financial worries and emotional distance from their parents. The characters in Normal People are deeply swayed by a need to perform and impress for the people around them. Peer pressure and social expectation undercuts Marianne and Connell’s relationship from the outset, ensuring it never properly flourishes. Ultimately, their love story is one undermined by constant confusion and misunderstanding.

Rooney’s success is helped by her economic, simple writing style; Conversations and Normal People are highly accessible books that many will have surely finished in one sitting. Yet manycritics have spoken about the gradual way her books get under one’s skin, with light prose that never draws attention to itself but ensures the story stays with you long after you close the last page. They also seem to be greater than the sum of their respective parts; there’s not really a plot to follow but rather a sensibility and tone to bear witness to.

Rooney’s biggest achievement is her ability to weave the digital forms of communication of the millennial era effortlessly throughout her stories. Connell and Marianne spend time with each other in person, but as they go slightly separate ways at university they rely more and more on text messages and emails. Usually, when characters of a book, film, television show use technology, it draws attention to itself and exaggerates its importance despite its’ limited relevance in the plot. The internet and social media lingers around in many modern novels, an issue that writers seem to feel the need to address in order for their work to be considered fresh and topical. But Rooney’s use of the internet in Normal People has been praised for feeling authentic and real. Social media and Skype aren’t just casually referenced for pop-culture appeal, but rather as a way of telling us more about who these characters are. Marianne and Connell speak differently when communicating over the internet, and Rooney has spoken about the effort she went to establish their “twitter voice”. We get a sense of how, more than any other time in history, barriers of time and space no longer prevent friendship and love from blossoming. Connell takes great enjoyment in his emails to Marianne, which go beyond a simple means of communication to a symbol of how their entire relationship operates:

“He couldn’t explain aloud with he finds so absorbing about his emails to Marianne, but he doesn’t feel that it’s trivial. The experience of writing them feels like an expression of a broader and more fundamental principle, something in his identity, or something even more abstract, to do with life itself.”

Two centuries ago, Jane Austen mastered the epistolary form, using letters and correspondence in stories as a way of providing readers with an intimate view of her characters’ thoughts and motives. And just as Pride and Prejudice is at its heart a tale of romantic misunderstanding, Rooney is able to show the frustration that comes with communicating in the 21st century. Normal People is very much a story of the things left unsaid. Marianne and Connell are so often unable to express how they truly feel, while little misunderstandings and false interpretations, so common in the social media age, snowball out of control, ensuring a deep, emotional relationship never flourishes like it should. Miscommunication undercuts the entire story, not just as a plot device but as a way of showing that, in the modern era, it is common to be both simultaneously connected and lonely; informed of people’s lives but never really possessed with true knowledge or a close connection with another person.

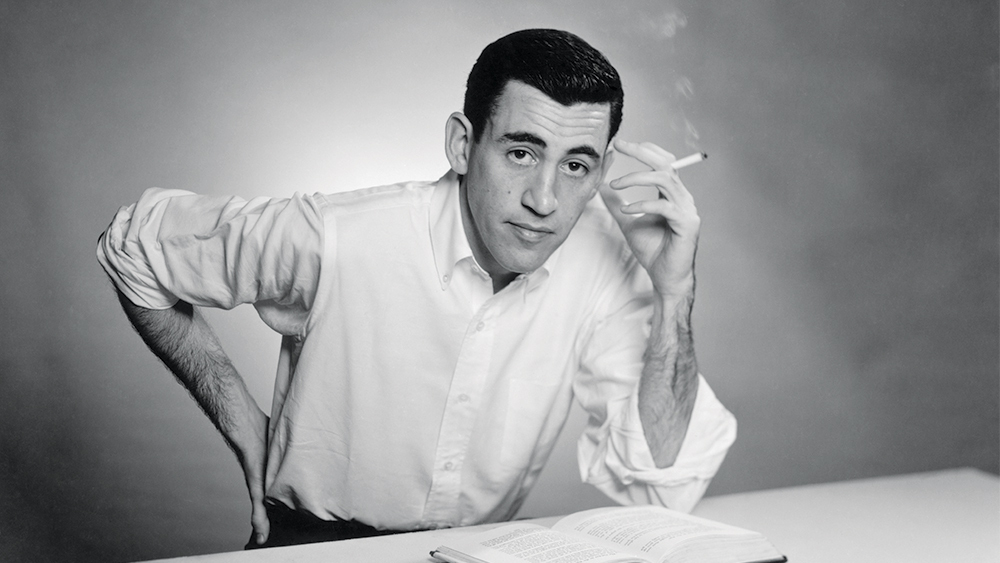

As supposedly the writer who has most powerfully reflected the realities and experiences of her generation, Rooney has drawn countless comparisons to J.D. Salinger, who in novels like Catcher in the Rye and Franny & Zooey and a bunch of short-stories in The New Yorker was said to encapsulate the mood and anxieties of post-war American youth. There are many similarities between the two writers, both in terms of the stories they tell and the way they tell them. Most visibly, their main focus is people; they write character studies of individuals and relationships, less about what people do but why they do them and who they are. They also both structure their stories around conversation and dialogue. Normal People, in particular, is essentially a series of meetings and conversations between the two love-struck young adults and their friends. Rooney herself identified Franny & Zooey – a book of only two or three very long conversations – as having a monumental influence on her writing style, particularly the way it prioritises talking and communication as a primary form of storytelling and character development.

Catcher in the Rye was said to be a generation-defining story when it was released in 1951 and, like Normal People, seems to be a book that needs to be read at a particular time of one’s life to really work. In the post-war years, novels like Catcher were able to creatively express the alienation, disillusionment and existential angst that young people were feeling at the time, anticipating the social changes and youth movement that defined the ensuing decade of the 1960s. Holden Caulfield became a cultural icon because he was outwardly rebellious and questioned adult authority as a sceptical, social outcast. Yet the struggles of early adulthood for Rooney’s generation seems more about accepting and worrying about cultural pressures than a conscious decision to defy them. Her characters are more cynical and sceptical of their elders than they are outwardly rebellious towards them. They are conscious of their precarious job prospects and unclear futures, but in a way that is self-referential and sarcastic. Young people today challenge the expectations of their elders, disputing the laissez-faire, latte-sipping, avocado-on-toast-eating identity that has been placed upon them. But they do so primarily through humour and participation in a self-referential online community, laughing at themselves but frustrated if others do the same. As Lauren Collins at The New Yorker pointed out, Rooney’s characters “are let down by the adult world, but intrigued, too, and maybe galvanised. Their default attitude is a raised eyebrow. They fear that they might be the biggest phonies of all.”

Not everyone has bought into the Rooney hype. The portrayal of young adults in Normal People has been seen by many older readers as fairly bland; a shallow self-reflective millennial mirror that lacks real substance. The typically iconoclastic social commentator Will Self lambasted Rooney in an online QandA with British newspaper The Times last month:

“You only need to look at the kind of books being lauded at the moment to see how simple-minded they are... I read a few pages of the Sally Rooney book. It may say things that millennial want to hear reflected back at them, but it’s very simple stuff with no literary ambition that I can see.”

Although Self’s criticism is exaggerated and designed to shock, criticism in this vein raises interesting questions about the way so-called millennial novels are received and what they are fundamentally about. There’s a tasty irony in the title of Rooney’s book given that the “Normal People” depicted in the novel are perhaps strange and foreign to most readers. The world of Trinity College's academic elite is far off the average reality of young people today. Her characters are frequently annoying and offputting, cringeworthy in their sense of entitlement and pretentiousness. At one point, Marianne hosts a dinner party at her parents’ vacation home in Trieste, Italy where an argument breaks out over whether the group of young adults are drinking out of “proper champagne glasses” or “coupes”. Moments like this are reminiscent of Bret Easton Ellis' polarising early novels, particularly Less Than Zero, where it is difficult to pinpoint whether the portrayal of entitlement of vacuous, fuelled teenagers is brilliant satire or just plain boring.

The reception of Normal People also echoes the polarising treatment of Lena Dunham’s HBO series Girls. The show burst onto the scene in 2012, making an immediate impression as an experience that could hold an anthropological mirror up to Generation Y and depict it in all its intricacies and imperfections. Dunham didn’t hold back on establishing this, with her character Hannah telling her parents in the pilot episode that “I don’t want to freak you out, but I think that I may be the voice of my generation. Or at least, a voice of a generation.” Like Rooney, Dunham is ultimately concerned with that delicate time between adolescence and adulthood, the formative years of one’s life that leads many to stumble and others to thrive.

Yet it was also undercut by harsh criticism from the beginning, people downplayed the so-called ‘reality’ of the television series, suggesting it was no more than narcissistic, pretentious millennial entitlement. An inherent problem existed in the fact that the group of young women exist within an incredibly wealthy, privileged, inner-circle of friends, a world that is closed off to most people watching the show. The show was plagued by such criticism fairly early in its’ six seasons, particularly after people voiced their frustration with the lack of racial diversity being presented on-screen. Dunham was only writing about what she knew and did come to express deep regret for the perceived ‘whiteness’ of her show. She at times drew back from the hype surrounding her ‘millennial voice’, adding in an interview with Buzzfeed that she thought such a claim was “lost with beatnik literature. Because of globalization and increasing populations, my generation kind of consists of so many different voices that need so many different kinds of attention.” Yet given the show had been touted as the voice of the ‘generation’ - one that every aimless, cynical Gen Y-er could relate to - it was bound to run into such problems if the reality depicted on-screen was a narrow one.

Sofia Coppola has received similar criticism throughout her career not =for her portrayal of entitled, privileged and disillusioned characters. Her films Lost in Translation, Marie Antoinette and Somewhere are all stories of rich, successful people struggling to find meaning and purpose in their lives; explorations of the disillusionment and ennui brought about by modern life. This has made her one of the 21st century’s most divisive filmmakers, as for every individual that is able to connect with her melancholic tales of loneliness and lethargy, there are countless others who level her with accusations of shallow pretentiousness and slow, empty storytelling. There are many similarities between what Coppola and Dunham are able to create on screen and what Rooney is able to accomplish through words on the page. Most obviously, they are all concerned with young women, in particular. This makes them immediately different to the vast majority of stories and tales of disillusionment and self-discovery; Catcher in the Rye, in the tradition of Joyce and Fitzgerald (and most classic literature) focuses its attention on the frustrated brooding of a young man. For all the criticism of Girls’ limited diversity, the show’s depiction of sex and gender from an almost exclusively female perspective was ground-breaking, a refreshingly honest and more realistic portrayal of relationships from a woman’s point of view than mainstream forms of entertainment had previously offered.

And there is also a hidden irony and social satire behind their shared depictions of an elite, wealthy world. Rooney makes Trinity College students seem dull and facile in the same fashion as the characters within the New York bubble of Girls, while the Hollywood of Coppola’s Somewhere and The Bling Ring is littered with shallow, fame-obsessed people. This entitlement and privilege often puts people off, masking the deeper point being made. Girls was never just a mirror for millennial to stare at themselves at, but rather a nuanced portrayal of flawed, self-absorbed young people living in a narrow world. Many people actually miss the subtle satire of the show, which finds a great deal of humour directly through the self-fixated entitlement of its’ characters and the disconnect that exists between the bubble of their own lives and what most millennials are doing on an average day. Like Normal People, it is more ironic and self-consciously posturing than it gets credit for.

It’s not surprising that writers like Rooney and Dunham can’t connect with everyone. Stories are always going to be loved by some and hated by others. Yet the notion that Rooney’s fictional world is an elite, intellectual one perhaps creates a paradox when coupled with the suggestion that she is the new literary ‘voice of the Snapchat generation’. In the millennial era, defined more by social difference, ideological conflict and displaced identities than at any other time in history, it is difficult to see any book speaking for an entire generation. Rooney writes brilliantly about the academic, intellectual world she knows, but in doing so, is forced to cut her characters off from being relatable objects of identification. As American novelist Tony Tulathimutte pointed out in a fascinating piece for The New York Times:

“There’s nothing wrong with wanting to see yourself reflected in a book, and there’s nothing about novels like mine that prevent people from doing so. But the desire to universalize that feeling, and declare that any book speaks for everyone, ends up short-changing both the novel and the generation.

Tulathimutte’s own novel Private Citizens was faced by a similarly polarising wave of hyper-praise and fierce scrutiny, perhaps because it advertised itself on the dust cover as “Middlemarch for millennials”. The reception of generational books seems to point to the broader gap that often exists between the intention of the author and how books are marketed and received. Although Rooney has distanced herself from the hype surrounding her generational talent, it has helped her achieve quick literary fame. Publishers need to sell books and labelling someone as the voice of a generation goes a long way to doing so, just as the tag of the ‘Great American Novel’ has romanticised readers into buying vintage classics for over a century. Generational tags have always been a commercial vehicle, after all; a way for businesses and marketing agencies to identify groups to sell products to. But by promoting a universal, one-size fits all approach to fiction, you automatically undermine the specificity and individuality with which authors write. Novels are just stories after all, usually grounded in a particular time and place but not necessarily attempting to speak for everyone that exists there in reality.

What will these great millennial stories look like in a few decades’ time? How will Normal People or Girls appear when they are no longer weighed down by their identification with millennial privilege and entitlement? Even if Rooney’s depiction of millennial life was more diverse and expansive, young people today are reading much less compared to their parents, turning their attention away from literature towards streaming and digital forms of entertainment. So, is there a limit to the extent any book in particular can accurately speak for a generation of people? Perhaps writers like Rooney have greater weight in hindsight, as the young people of the future can retrospectively look into the time-capsule and interpret how people lived today. Catcher in the Rye, for example, was a revolutionary and best-selling text on its release in 1951, but it still sells 1 million copies every year and is destined to be discovered by young adolescents for generations to come. There’s a chance Normal People will have a similar effect, as a seminal text for what it means to be young and confused and in love in the early 21st century. Just don’t call it the great millennial novel.