Out in the streets: David Small's Home After Dark

David Small’s graphic novel Home After Dark tells the story of a young boy, Russell Pruitt, struggling through his early adolescence in a world that is strange, violent and uninviting. Osmall-town suburban America during the early 1960s. Russell moves to a new school and a new home in Marshfield, California. His mother having abandoned him and his dad offering little love or support, Russell is largely left to fend for himself, navigating the dark, unfriendly neighbourhood on his own. The novel is Small’s follow-up to his debut graphic memoir, Stitches, which recounted his adolescent struggles as a cancer patient and sixteen-year-old runaway. Released in 2009, it was an outrageous critical and financial success; a #1 New York Times Best Seller and a subject of praise from critics who lauded the portrayal of childhood voicelessness and alienation. Stan Lee went as far as to say that Small “elevated the art of the graphic novel", a momentous claim from a giant of the art form. Although Home After Dark shares many of the same concerns and uniquely stark and surreal drawing styles of Stitches, Small translates his portrayal of adolescent chaos to a darker, more violent setting; a black-and-white kaleidoscope of childhood fear, desire and anxiety that constantly blurs the line between illusion and reality.

The fear of outsiders and the ‘other’ lurks on every page. Adults park on the street to yell racist insults at a Chinese family. Children are bullied by older classmates when they arrive at school; labelled freaks, spazzes, queers. From the opening pages, Marshfield is a violent town, haunted by a toxic pack of teenagers and a serial cat killer, symbols of the xenophobia and crisis of masculinity which plagued post-war American culture. Small is able to uncover the violence, alienation and disillusionment that lay hidden beneath the surface of American society during these years, voiceless in the face of Eisenhower-era optimism and rampant consumerism. A xenophobic fear of outsiders pervaded society, as those who were different (immigrants, communist sympathisers, homosexuals) were targeted as undesirable members of society, while the growth of the American middle-class made it fashionable to be as normal as people. Home After Dark is grounded within this culture; it is all about fitting in and the perils of following the crowd. The pages are littered with people who are nasty and cruel; bullies, who - as the maxim states - take their own insecurities out on the vulnerable people around them.

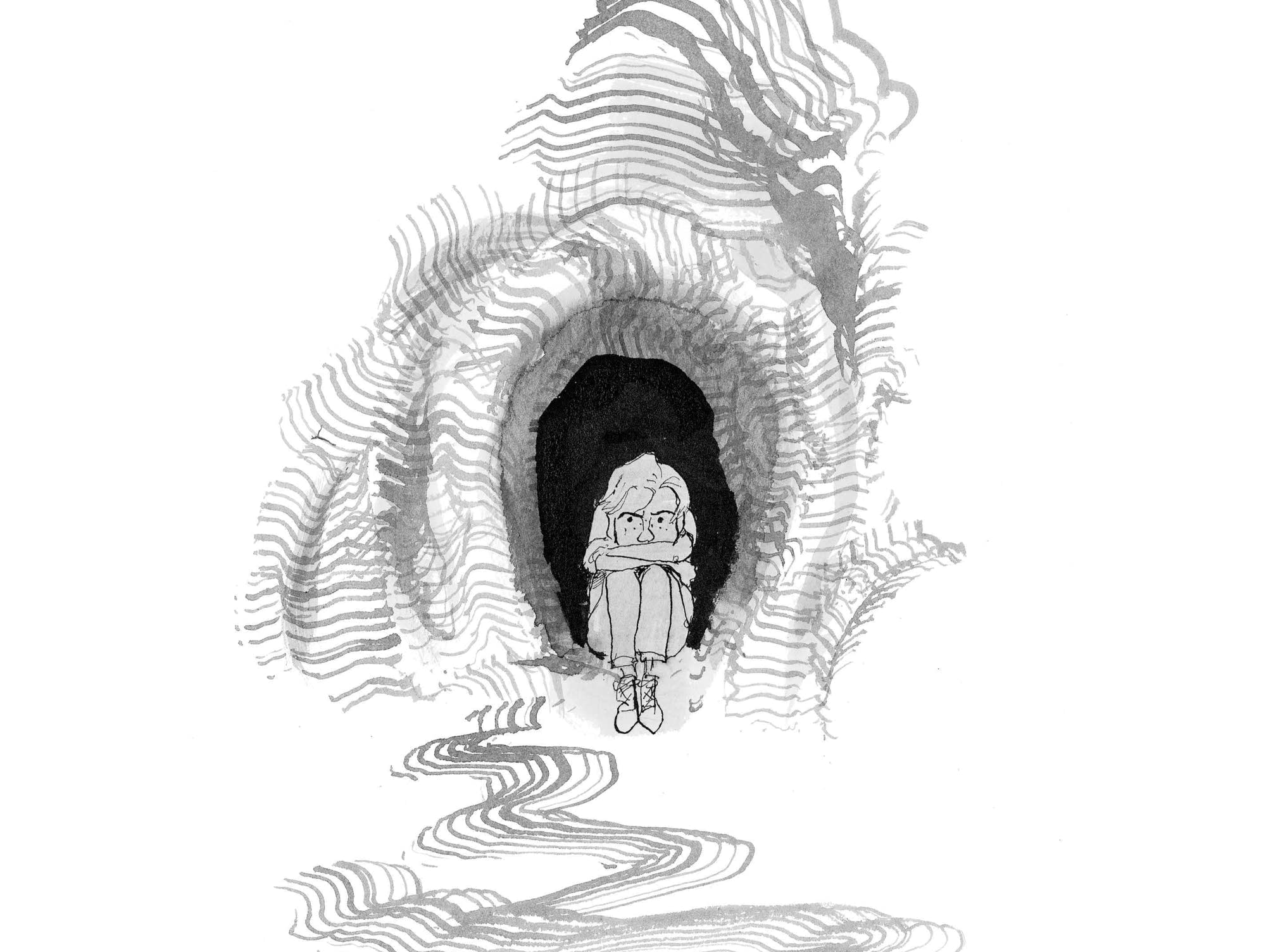

Yet Small’s brilliance lies in his ability to show how flawed, confused, vulnerable people can also be made complicit by the pressures of fitting in. There is a chasm in the novel between how the boys act, talk, and present themselves to one another and what we can see they are feeling and struggling with internally. The story is essentially a series of small actions which lead to tragedy; a harrowing tale of choices and consequences. Eager to be accepted and avoid being wailed on, Russell joins the pack of tough boys who strut arrogantly around the streets of Marshfield and hold court at a secret treehouse, where they smoke their first cigarettes, drink their first beers and talk about girls. Worried and deeply impressionable, Russell never feels like he really belongs with his more outwardly confident, relaxed friends. He constantly compares himself to the leader of the pack, Kurt. In an extremely poignant dream sequence, he imagines his bed-sheets as a tunnel which will allow him to wake up in Kurt’s body. Self-consciousness and anxious indecision eventually leads him to shun and ‘out’ his one true friend – who reveals his true self to him in a moment of awkward desperation and affection. He is also inconsiderate and ungrateful to their friendly Chinese neighbours the Mahs; the only people offering him any real care and love. By the end of the novel, we see how a mixture of social isolation and internalised anger can have tragic consequences, particularly for those individuals pushed to the peripheries of society.

Before writing Stitches, Small was a decorated children’s writer and illustrator, mostly of silly, whimsical stories about things like frogs, dragons, fairies. His movement into graphic novels continues this focus on children but translates it to a much darker, violent world. They are adult stories about children and growing up, drawing comparisons to classic coming-of-age tales like Catcher in the Rye. The boys of Marshfield are left to face the most confusing times of their lives alone, vulnerable to the distortion mindset of adolescence and the pulls and pressures of the outside world. Adults are nowhere to be seen. Russell’s dad spends the first half of novel as a mean-spirited, deadbeat alcoholic, before disappearing altogether. When others appear they are often more cruel than the kids, yelling racist insults at the Mah family – the only morally redeeming characters - and egging on a fight when one of the boys is outed as gay. Later, when Russell sees a group of kittens, “their head shoved through a fence”, his Dad passes it off as the local kids “just messing around” and tells his son to “stop being such a wimp.” Small’s depiction of adolescence conflict also echoes a lot of Lord of the Flies, William Golding’s famous portrayal tension between individuality and groupthink within a marooned class of boys. The brilliance of the story is not so much in the depiction of violent self-governance but rather in the way it gradual develops and rise over the course of the novel. When the schoolboys, stuck on an island without adult supervision, eventually resort to savagery, it seems natural and inevitable, as if there was no other possible route the story could have taken. In the same way, Small is able to build a world that is haunted by a dark brand of toxic masculinity, right from the opening pages. Over the course of the novel, however, this steadily rises to an unavoidable crescendo of violence, vitriol and tragedy.

Home After Dark is reminiscent of some of the best on-screen tales of darkness and violence within small-town America. In the disturbing melodramas of 1950s Hollywood and other pitch-black mysteries by Hitchcock and David Lynch, a dark, violent, world is revealed beneath the picturesque, white-picket-fence surface of suburbia. The American Dream becomes a claustrophobic, inescapable nightmare. Jo Cotten reminds his niece in Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt that “the world is a foul sty. Do you know, if you rip off the fronts of houses, you’d find swine? The world’s a hell.” This same premise drives Lynch’s Blue Velvet, as the lid of the picturesque logging town of Lumberton is pulled off, exposing a seedy, murderous underbelly.

Many other filmmakers have subverted the moral superiority and monotony of suburbia through extravagance and excess. In many of the Hollywood melodramas of the 1950s, such as Peyton Place and the films of Douglas Sirk and Nicholas Ray, the expressionistic use of rich, vibrant colours and a string-heavy orchestral score a suffocating, claustrophobic world of hysteria and anxiety. Small’s style is more subtle. Marshfield is not colourful but a dull, ramshackle wasteland, plagued by dilapidation and adult neglect. Yet a dreamlike beauty and rhythm seems to haunt the pages of the novel, even if the story it tells is one marked by chaos and violence. Small is able to exaggerate the distorted mindset and cruelty of adolescence through extravagant mise-en-scene, characterised by rich shadows and expressionistic angles. Stark, moody portraits of Russell hone in on his emotional response to the brutal world around him, providing a window into the tortured, confused mindset of an isolated teenager. We see the contrast between Russell's internal chaos and the stable image he tries to present to others in order to fit in. Small’s monochrome colour palette exaggerates the shadowy setting but also helps to maintain a consistent tone of anxiety and pain, keeping us with Russell and his experience.

There is also an inherently visual aspect to the way the story unfolds. Graphic novels are in essence cinematic art forms. Like on film, the action is condensed down to single frames of detail which, when combined in a sequence, tells a story. Yet, reading Home After Dark makes one feel like they are actually watching a movie, inspired by the tension and darkness of a Hitchcock film. Small has acknowledged cinema as a key inspiration for his narrative style, saying of Stitches that it really is “a silent movie masquerading as a book.” He doesn’t really make use of words. Those that do remain are used mainly as a way of advancing and pacing the plot, which is primarily told mainly through a collection of sketches that momentarily capture the emotion and decisions of Russell and the people around him. While the story moves quickly, it slows down in important emotional scenes, with striking close-ups of Russell’s facial expressions bringing it to an intense, arresting standstill. His illustrations - washes and ink renderings drawn in a loose, free style - remind one of everything that is not said out loud but instead felt on the inside. We glimpse Russell’s deepest fears and darkest desires - the inner workings of his raw subconscious. Dead cats and barking dogs seep into his dreams, as visions of caged lions and vicious beasts reflect his inability to break away from the carnal mob mentality of the town. Small’s illustration aids this transition into surreal fantasy, as the morphing of images and blending of adjacent panels layer imagination and hallucination over the top of real-life experience, mirroring the work of his cinematic heroes: Fellini, Bunuel, Antonioni.

The distortion of reality and fantasy also echoes the broader moral uncertainty in Home After Dark. The novel is a raw and honest portrait of adolescence, even if it is coloured by surreal dreams and hallucinations. Many stories about childhood end up falling into the trap of nostalgia and sentimentality, painting one’s formative years as a blessed time or focusing on reclaiming a sense of innocence lost in adulthood. Small shows that, for many teenagers, growing up is living misery, whether it be family conflict at home or alienation from a peer group. He doesn’t sugar-coat his depiction of the ways in which teenagers, particularly boys, use cruelty and the exclusion of others as a way of fitting in. Yet empathy is provided to most characters - we can see why they act the way they do. Russell, for one, is clearly a victim of circumstance rather than choice, abandoned by his mother and father and left to navigate the turbulence teenage years alone. And while all the teenage boys act tough on the outside, constantly pushing away the people around them, Small hints that they all clearly crave human connection and friendship. Their story becomes one that is simultaneously a disturbing, painful nightmare and a beautiful tale of transformation and personal growth.

He also smartly avoids ending with any sort of warm or moral resolution. Russell eventually receives the love and care he desperately needs after being taken in by the friendly Mah family, but is still forced to live with his guilt. Home After Dark shows that one of the most important lessons we learn when growing up is that we have to live with and face up to our mistakes, even if they have hurt others. You can’t place your trust in all the people around you and sooner or later you have to figure out who you are and what sort of person you want to be. Peer pressure and social isolation can be poisonous to a vulnerable teenager, but they are never excuses for participating in bullying or a toxic brand of masculinity.

Home After Dark is a powerful addition to the wave of art and entertainment that has has emerged in recent years aiming to tackle the messy, humiliating realities of adolescence. Netflix hits like Big Mouth and American Vandal, as well as bloggerBo Burnham's directorial debut Eighth Grade, are displaying teenagers in all their cringe-worthy social anxiety and humiliation, exploring taboos and promoting positive self-image. All these stories demonstrate that the chaos of adolescence- with its strange mix of community and loneliness; hope and despair; rejection and acceptance - is something we all have to go through. The power of Russell’s story lies in how Small transports this premise to a darker, cinematic world that reflects the internal monologue of social anxiety and alienation; a Kafkaesque kaleidoscope of fears, dreams, and emotion.