Comedy's Greatest Era

"As soon as the screen began to talk, silent comedy was pretty well finished."

In his famous essay published in Life magazine in September 1949, film critic James Agee lauded the talents and pantomime magic of the great Hollywood silent film stars. In the work of Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin, among others, cinema had achieved an unsurpassed brilliance and “perfection”. They were physical geniuses, who allowed stories to be told purely through the expression of the face and movement of the body. They made a generation of audiences roar with laughter, but possessed a steadfast desire to do so economically and with limited help, bringing creative vision and flair to the most simple of plots and setting.

The article is in essence a eulogy. “Comedy’s greatest era”, according to Agee, had vanished by the early 1930s, dwindling away in the face of the ‘talkies’. The invention of sound synchronisation and its emergence as a viable commercial form of entertainment had fundamentally changed Hollywood. It had shifted the focus of comedy to talking, thereby drying up physical movement and action within the frame and giving rise to an over-reliance on dialogue to tell stories and make people laugh. To Agee, this meant films came to rely on a more intellectual sense of humour that was not grounded in everyday life and inferior to what could be produced purely from physical action and histrionics:

When a modern comedian gets hit on the head, for example, the most he is apt to do is look sleepy. When a silent comedian got hit on the head he seldom let it go so flatly...It was his business to be as funny as possibly physically, without the help or hindrance of words. So he gave us a figure of speech, or rather of vision, for loss of consciousness. In other words he gave us a poem, a kind of poem, moreover, that everybody understands.

The essay is a brilliant piece of film appreciation and history. Agee, in the mode of the great film writers Pauline Kael, Manny Farber or David Bordwell, has an unncanny ability to communicate exactly what one may have noticed and felt deep down about a film but have never been able to fully understand or express. He found an audience in the American public, bringing back a fervent public interest in these silent stars. It helped to elevate their slapstick humour away from a “low” form of comedy towards one that was appreciated by mainstream audiences as a revelatory cinematic art form from the 1950s onwards, through reissues on television and in cinemas. Nevertheless, in his attempt to eulogise the Keatons and Chaplins of the silent era, Agee undermines the amazing cinema and comedy that emerged in the 1930s after Hollywood's adoption of sound. In identifying the silent era as the best era for finding hilarity in Hollywood, he underestimates just how funny words can be.

Hollywood began to expand the romantic comedy genre in the 1930s and 1940s, shifting focus to dialogue and verbal sparring in order to parody conflict and tension within the traditional love story. The best of these films were classified as "screwball" comedies, named after the baseball pitch that is fast, difficult to predict and likely to dart off in uncertain directions. A satirical take on the traditional romance story, screwball featured a hilarious 'battle of the sexes', as men and women would argue, bicker and one-up each other before inevitability falling in love and usually getting married. This was the real "greatest era" of American comedy - a fantastic blend of 'low' slapstick comedy with the "high" classy sophistication that typified of the Golden Age of Hollywood.

Whereas silent comedy was driven by the individual personalities and 'hero' status of stars like Chaplin and Keaton, talking pictures became more communal and geared towards verbal conflict interaction within groups of people. The multiple-hero dynamic became a mainstay, as the Marx Brothers and acts like Wheeler and Woolsey created humour between themselves rather than in opposition to the outside world, as witty dialogue was paired with silly slapstick to great comedic effect. Some individual comedians still held court, like W.C. Fields, but their comedy relied on verbal humour and fast-talking antics that were simply not possibly without sound.

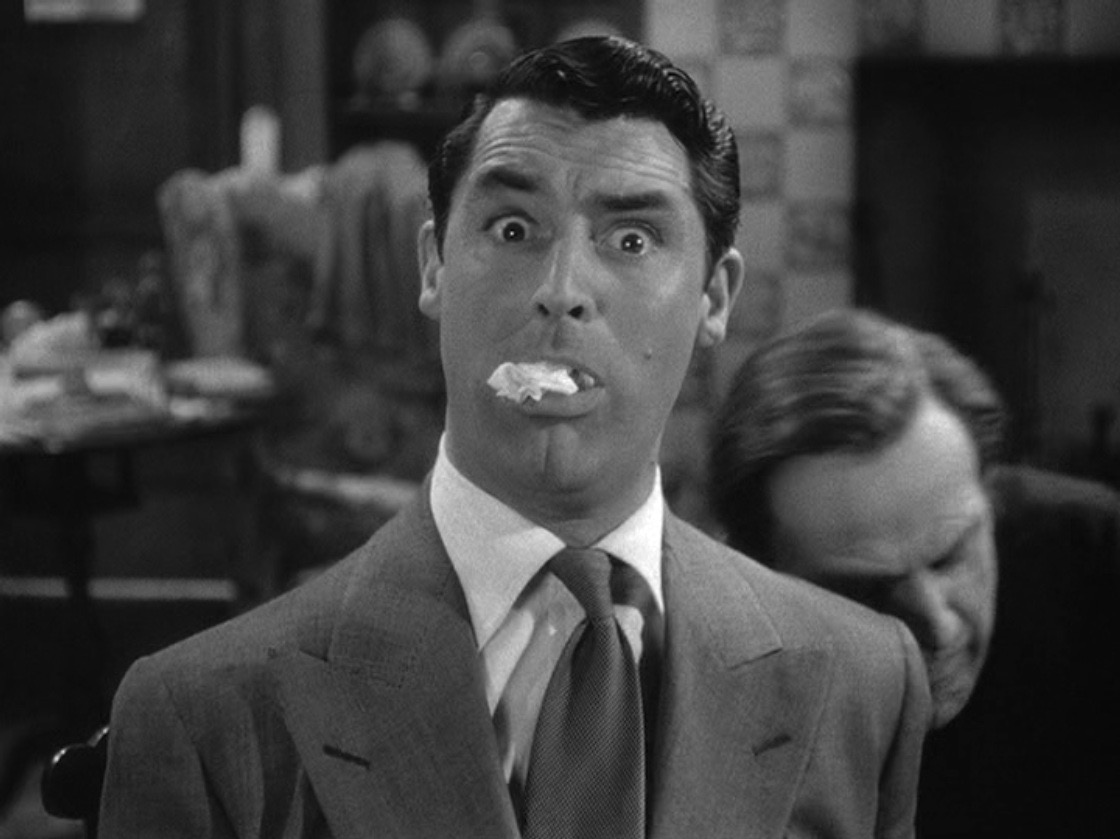

His Girl Friday, one of the screwiest of screwballs, features a revolutionary use of fast, overlapping dialogue, as characters talk over the top of another with amazing rhythm and comedic timing. Directed by screwball icon Howard Hawks, who was also responsible for the classics Bringing Up Baby, Ball of Fire and Monkey Business, the film tells the story of a newspaper editor (Cary Grant) who, about to lose his ex-wife and lead reporter (Rosalind Russell), gets the couple entangled in a murder case with the aim of winning her back. Although this plot is fairly forgettable, the film has won a beloved place in the canon of Classical Hollywood cinema due to its' inventive wordplay and hilarious witty repartee. In an attempt to reflect the way people speak in real life, Hawks revealed that the dialogue was written “in a way that made the beginnings and ends of sentences unnecessary". A single viewing doesn’t do the film any justice - there are so many jokes packed into the 92-minute script that one is bound to miss half of them. This was revolutionary comedy, derived not just from what people said but how and when they said it. As Pauline Kael wrote about the film, the “spastic explosion [of] word gags take the place of the sight gags of silent comedy.”

Even though screwball is famous for this style of quick, snappy dialogue, it also manages to inherit the physical humour of the silent era. Rather than needing to balance talking and movement, the humour and charm of the great screwball comedies bursts out of this mixture. The genre relied on an ironic combination of wit and slapstick; class and clumsiness. Love, sexual chemistry and desire was conveyed elegantly, while pratfalls and ridiculous physical antics inherited from the silent era undermined and parodied this stylishness at every opportunity. It is no coincidence that the two first screwballs, Twentieth Century and It Happened One Night, were released in 1934, the same year that Hollywood was first enforced to adhere to the restrictions and limitations of the Motion Picture Production Code. Largely based in conservative, Catholic doctrine, the code was designed to stop the "moral standards" of audiences from slipping, through mandates surrounding how villains and authority figures were presented and restrictions on taboo subjects like sex, violence and adultery being depicted on-screen. Hollywood needed to get clever to bypass the code. Screwball - famously characterised by critic Andrew Sarris as a "sex comedy without sex" - thus emerged as a genre where both physical and verbal comedy could parallel sexual tension and conflict.

The characters of these films literally fall for each other. In The Lady Eve (1941), Barbara Stanwyck's seduction of a naive Henry Fonda is punctuated by slapstick. She drops an apple on his head, repeatedly trips him over and leads him around in a stumbling daze by her feminine charms. Similarly, in the very silly Bringing Up Baby (1938), another gem by Hawks, Katherine Hepburn and Cary Grant essentially spend the entire film running around, falling over, cross-dressing and destroying their clothes as they fall in love. If Agee was worried that sound would make comedy more intellectual and pretentious, one only needs to watch these films to recognise how silly some of them were. Bringing Up Baby is a story about a palaeontologist being romantically pursued by a scatterbrained heiress and her pet leopard. In The Awful Truth, a divorcing couple sabotage each other's romantic escapades in a desperate attempt to stay with each other. In these films, as in all screwballs, comedy is driven not only by witty back-and-forth dialogue between characters but also through zany situations undercut by physical antics and slapstick. Beneath the silliness lies a genuine warmth and romantic intimacy.

Before the coming of sound, comedians always looked funny. When Chaplin's tramp - or, even in the the early sound era, Jimmy Durante & the Marx Brothers - walked into the frame, they didn't have to do much to make audiences laugh. They were clowns. In screwball, however, the people falling over and hurting themselves are beautiful, rich, elegant people. The action is taken off the streets to the fairytale world of the idle rich. The entire genre has been viewed as an attempt by Hollywood to provide "escapist" upper-class stories for an American public struggling through the harsh economic realities of the 1930s. The slums of the slapstick silent film became the extravagant, sophisticated manor houses of screwball romantic comedy. Sharp suits and extravagant dresses were ruined by pratfalls and classy people were made to look like fools. It was proved that people could be beautiful and sophisticated on-screen and not necessarily take themselves seriously.

There is no better example of how screwball blended the 'high' with the 'low' than the genre's most visible star, Cary Grant. Grant was the undisputed king of screwball and the icon of Hollywood during the golden era of the 1930s and 40s. David Thomson called him “the best and most important actor in the history of movies, ” and it is hard to imagine any of his films - particularly the romantic ones - without his stylish charm and comedic timing. Just like his silent predecessors Chaplin and Stan Laurel, Grant had originally come to the States as a member of a British vaudeville troupe, having starred as as an acrobatic comic in variety theatres throughout England. After starring in many forgettable pictures in the early 1930s, he emerged out of the studio system quagmire to become one of Hollywood’s most visible and influential stars.

Grant has always possessed a paradoxical on-screen image equally defined by a classy, romantic sensuality as much as by silly, clownish antics. His suave added a sophisticated angle to the "low" comedy of slapstick, just as his physical gimmicks made him more of an everyman than his bewitching good looks might suggest. He is just as well known for his stylishness in Hitchcock collaborations like Notorious and North by Northwest as he is for his involvement in brilliantly quirky films like Arsenic and Old Lace and The Awful Truth. Pauline Kael honed in on this puzzling blend in her landmark article “The Man From Dream City”, identifying that “during those peak years, he proved himself in romantic melodrama, high comedy, and low farce”. Grant had an amazing ability to make people laugh just as much at his speech (though perfectly timed jokes and tonal inflections) as his physical movement and facial expressions (cocked head, double take, pratfalls) inherited from his vaudeville days. He is in this way the talisman of screwball and the connecting link between the silent film stars and the classy, male heroes that came to dominate Hollywood.

It is sad that the master comics of the silent era were crippled by the coming of sound and starpower of actors like Grant. Charlie Chaplin, Harry Langdon, Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton, the core silent comedians Agee praises, all experienced declines in either status, wealth or critical success. Each of them made “talkies” that were visibly weaker and less popular than their silent films. Chaplin survived primarily due to his wealth and unrivalled popularity. He continued to make non-talking comedies that became the all-time best of silent film (City Lights, Modern Times) while others were adapting to sound, and his efforts with the new medium, The Great Director and Monsieur Verdoux, are still brilliantly funny and memorable pictures. Nevertheless, after relying solely on the emotive expressions of the face and physical movement of the body, audiences just weren’t ready to deal with their silent heroes talking out loud. In Singin’ in the Rain, a classic comedy centred around Hollywood's transition from silence to sound, the shrill voice of the pantomime star Lina Lamont leads her colleagues to go to hilarious lengths to conceal it and she is made a laughing stock by audiences when it is finally revealed publicly.

Some silent stars, however, were able to make a seamless transition to sound. Greta Garbo, an icon of the silent era, surprised audiences with a deep, husky voice that perfectly matched her on-screen image perfectly. Her first 'talkie', Anna Christie, was famously marketed to audiences as “Garbo speaks!”. Carole Lombard, who originally made her name in silent slapstick comedies, became known as the “Queen of screwball” after quirky performances in Twentieth Century and My Man Godfrey. Known in Hollywood for her coarse language and wicked enjoyment of practical jokes, Lombard's dizzying and glossy performances led the way in a genre where women usually stole the show.

The comedic duo Laurel and Hardy also didn't look back, continuing to create incredibly physical comedy that used the new medium of sound and dialogue as a complementary device rather than the main tool. Their combination of slapstick and witty “catchphrase” dialogue would continue to inspire comedic performances like Abbott & Costello, Martin and Lewis, The Three Stooges, not to mention more recent examples like Homer Simpson. Promoting his recent film Stan and Ollie, in which he plays the English comic Stan Laurel alongside Steve Coogan as Oliver Hardy, John C. Reilly pointed out that the duo noticed how silent film stars were being left behind by the heavy focus on dialogue. Instead, they choose to use it sparingly:

“And Stan and Laurel thought - very wisely thought, you know what? We're doing this silent stuff very well. Let's not throw out the baby with the bathwater. Let's try to keep doing what we do really well. And where dialogue will enhance what we're doing, let's have dialogue.”

This blend also assisted the duo in realising their true comic potential. While they still relied heavily on physical gags, the skillful addition of a crash or a groan or a "d'oh!" enhanced their appeal at a time when other film stars were going broke.

Often the most interesting films (and art forms more broadly) are those that blend genre, style and tradition to make something new and revelatory. When watching romantic comedies from the 1930s, one gets a sense that they are witness to the history of an industry at a crucial and decisive turning point. Behind the zany antics and silliness of screwball lies a deep reflection of Hollywood in flux; a blend of nostalgia for the silent era of the past and enthusiasm for the innovation of sound. Each component of the genre wasn't unique or fundamentally new; it was driven by humour that had already been core features of 20th century theatre, vaudeville, and cinema. But it became something that was greater than the sum of its parts. Yet, as the film historian James Harvey notes, due to the elegant romance and beauty presented on-screen, “all the familiar, borrowed elements came together in combinations so new and fresh, so electric, and so intrinsically movie like that familiarity become revelation.”

Perhaps this is why these films still appear fresh to modern audiences, while other studio-era dramas seem tepid and sentimental, weighed down by outdated references and the technical limitations of the era. Or perhaps screwball's timelessness comes because it laughs at itself, reducing the classy sensuality of classic Hollywood to nothing more than silly farce. Agee may have been right that the silent genius of Chaplin and Keaton was gone, never to be rivalled, after the birth of the talkies. What emerged in its place, though, was even better: an eccentric, wild, sexy era of comedy that beautifully blended the possibilites of old and new, high and low, sight and sound.